“Texas Charlie” Bigelow, a U.S. Army scout, was patrolling Indian Territory when he contracted a fever that left him so weak he could barely open his eyelids. An Indian chief took pity on Bigelow and nursed him back to health using a mysterious medicine he called sagwa. When Bigelow begged for the recipe of this wonder drug, the chief sent five tribal medicine men to accompany the scout to the East Coast, where they created “Kickapoo Sagwa,” the magic elixir sold in medicine shows that traveled America from 1881 to 1912.

Or so the story goes, as recounted in countless Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company advertisements. But the story—like the medicine itself—was totally bogus.

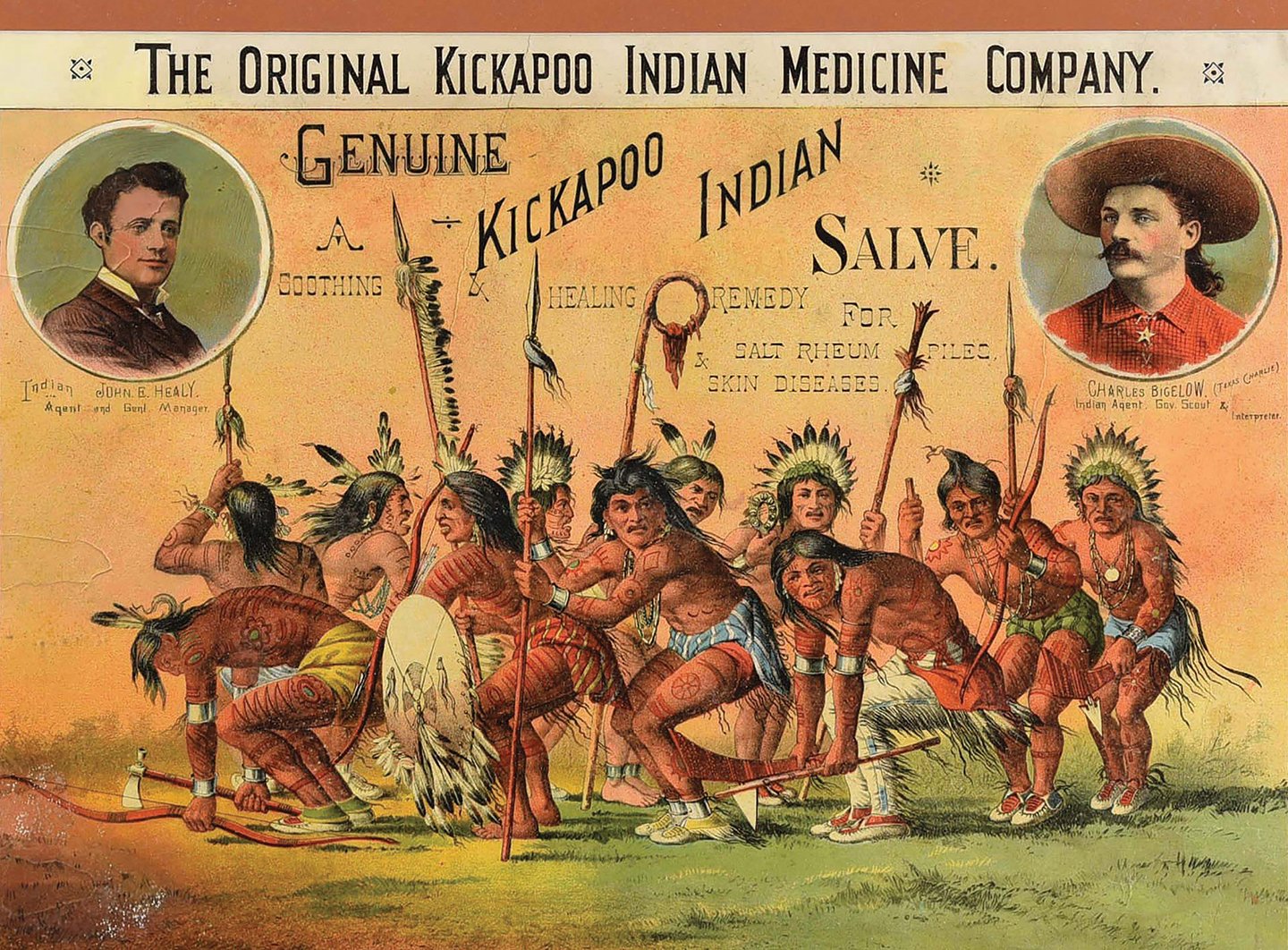

Bigelow was never an Army scout and never healed by an Indian chief. He grew up on a Texas farm in the 1850s, then fled the rigors of the plow for a life peddling patent medicines across the West and on the streets of Baltimore. In 1881, Bigelow teamed up with John “Doc” Healy, a former Union Army drummer boy, shoe salesman, proprietor of a traveling theatrical troupe called “Healy’s Hibernian Minstrels,” and the inventor and chief pitchman of a bogus liver medicine and a dubious liniment he dubbed “King of Pain.” When he joined forces with Bigelow, Healy concocted a new product, a fake “Indian” medicine he called “Kickapoo Sagwa.” And he proposed a brilliant idea for promoting it.

“His plan was to hire a few Indians, rent a storeroom, and have the medicine simmering like a witch’s brew in a great iron pot inside a tepee,” recalled “Nevada Ned” Oliver, a veteran pitchman hired by Healy and Bigelow.

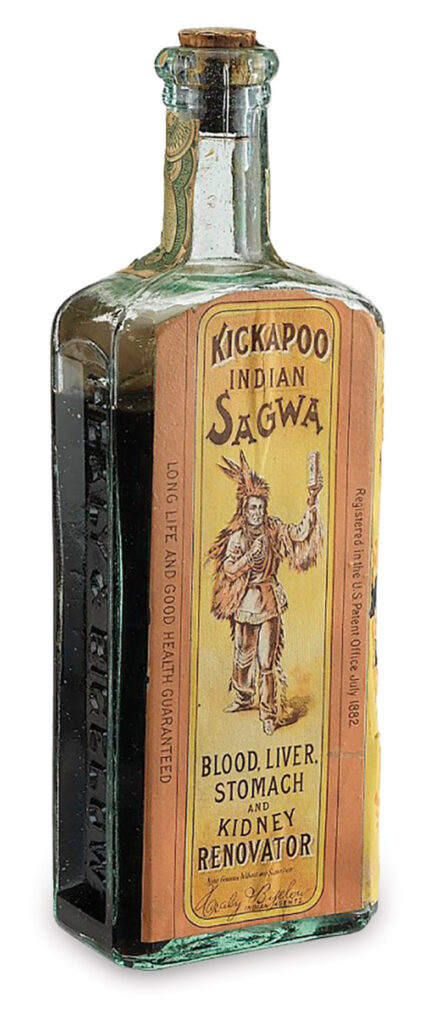

Healy set up his first Kickapoo showroom in Providence, R.I., then moved to Manhattan before settling in New Haven in 1887. In a huge warehouse decorated with tepees, shields, spears, and other Native American curios, Healy hired Indians—none of them from the Kickapoo tribe—to entertain audiences with songs and dances while stirring huge pots of fake medicine. He advertised his Sagwa as a secret Indian recipe consisting of “Roots, Herbs, Barks, Gums and Leaves,” but it was actually a completely Caucasian concoction containing sugar, a mild laxative, and a dollop of alcohol.

From their headquarters, Healy and Bigelow dispatched teams of real and ersatz Indians, plus vaudeville performers, and pitchmen posing as doctors to stage shows across America. The shows proved popular and the “doctors” sold oceans of Kickapoo Sagwa, as well as spinoff products—Kickapoo Buffalo Salve, Kickapoo Indian Cough Cure, and Kickapoo Indian Worm Killer. Healy and Bigelow became, as historian Stewart Holbrook wrote in his classic 1959 book, The Golden Age of Quackery, “the Barnum and Bailey of the medicine show business.”

The two partners didn’t invent the traveling medicine show: For decades, patent medicine pitchmen roamed rural America, attracting crowds with musicians and other entertainers. Nor did Healy and Bigelow invent the notion that Native Americans were “children of nature” who possessed a mystical knowledge of healing plants. Throughout the 19th century, Americans bought books purporting to reveal the secrets of Indian medicine—The Indian Guide to Health and The Indian Doctor’s Dispensary, among others. What made Healy and Bigelow rich was their ingenious combination of the age-old appeal of miracle cures with the whiz-bang theatricality of Barnum’s circus and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.

Early in the 1880s, Kickapoo shows were modest affairs—a few Indians performing dubious native dances, a few White singers and acrobats and a fake doctor, who sold Sagwa and served as master of ceremonies. One of those “doctors” was Nevada Ned Oliver, who described the shows decades later in a magazine article.

“The show customarily began with the introduction of each of the Indians by name, together with some personal history,” Oliver recalled. “Five of the six would grunt acknowlegements; the sixth would make an impassioned speech in Kickapoo, interpreted by me….It was a most edifying oration as I translated it. What the brave actually said, I never knew, but I had reason to fear that it was not the noble discourse of my translation, for even the poker faces of his fellow savages sometimes were convulsed.”

By the 1890s, Healy and Bigelow were dispatching more than a dozen Kickapoo shows across America every summer. The larger troupes played for weeks in big cities, staging elaborate spectacles in tents that held 3,000 seats. Admission cost a dime and shows included a dozen performances, interrupted by three or four pitches for Kickapoo cure-alls. The shows were wildly eclectic. The Indians performed war dances and an “Indian Marriage Ceremony,” and sometimes staged brutal attacks on wagon trains. The White performers included singers, acrobats, contortionists, comedians, and fire-eaters. Occasionally, Texas Charlie Bigelow himself appeared, a cowboy hat perched theatrically atop his shoulder-length hair. Billed as the world champion rifle shooter, Texas Charlie demonstrated feats of marksmanship and told dubious tales of his adventures.

“Later, there were aerial acts, a great deal of Irish and blackface comedy, and such exotic novelties as a midget Dutch comic, the ‘Skatorial Songsters,’ who performed while gliding around the stage on roller skates, and Jackley, ‘the only table performer on earth’ who turned somersaults on a pile of tables that extended 25 feet in the air,” Brooks McNamara wrote in Step Right Up, his 1975 history of medicine shows.

(National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

“If the combination of burning wagon trains and blackface minstrel routines was somewhat eccentric, “ McNamara continued, “no one seems to have cared or even noticed—especially not Healy and Bigelow, who refused to trouble themselves about complex artistic questions so long as the Kickapoo shows continued to attract crowds and sell medicine.”

The crowds kept coming, and kept buying Kickapoo potions, into the 20th century, enabling Healy and Bigelow to purchase expansive mansions near Kickapoo’s Connecticut headquarters.

In 1906, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, regulating the contents and the advertising of medicines—which put a damper on the more…um…poetic claims of Kickapoo’s pitchmen.

By then, Healy had sold his half of the operation to Bigelow and moved to Australia. In 1912, Bigelow sold the company for $250,000 to a corporation that continued selling Kickapoo Sagwa in drugstores but ended the traveling medicine shows.

Texas Charlie moved to England, where he manufactured a potion much like Sagwa. He called it “Kimco,” a tip of his cowboy hat to the scheme that made him rich—the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company.

Decades later, the hillbilly characters in Al Capp’s “Li’l Abner” comic strip drank a potent moonshine called “Kickapoo Joy Juice.” In 1965, the Monarch Beverage Company introduced a citrus-flavored soft drink called “Kickapoo Joy Juice.” It’s still around, and quite popular in Southeast Asia. The company never claimed the soda cures ailments, but it does brag that it contains enough caffeine “to give you the kick you crave.”

This story appeared in the 2024 Winter issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.