Keller Scholl got out of quarantine 13 days ago, and he’s still not feeling 100%. The itchiness — far and away the worst symptom, he says — is mostly gone, and now the graduate student just feels exhausted. “I’m trying to get enough sleep,” he says.

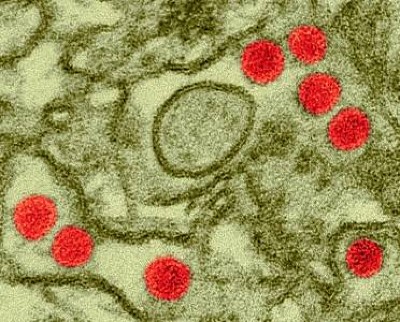

Scholl’s symptoms might be uncomfortable, but they are also of his own making. That’s because he signed up to be a volunteer in the first human ‘challenge trial’ involving Zika virus, a mosquito-borne pathogen that can cause fever, pain and, in some cases, a brain-development problem in infants. In standard infectious-disease trials, researchers test drugs or vaccines on people who already have, or might catch, a disease. But in challenge trials, healthy people agree to become infected with a pathogen so that scientists can gather preliminary data on possible drugs and vaccines before bigger trials take place. “Accelerating a Zika vaccine by a month, a few days, that does a lot of good in the world,” says Scholl, who studies at Pardee RAND Graduate School in Santa Monica, California.

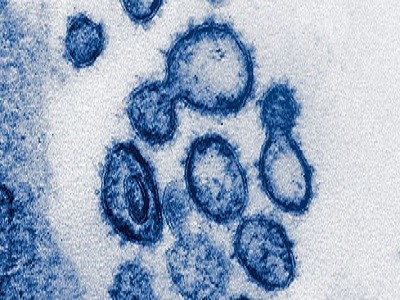

Scholl is not alone in his altruism. He was among thousands of people who answered a global call for challenge-trial volunteers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The effort was spearheaded by an advocacy group called 1Day Sooner, which aimed to generate support for intentionally infecting people with the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 to accelerate vaccine development. Those challenge trials eventually started in 2021 in the United Kingdom.

Scientists deliberately gave people COVID — here’s what they learnt

But with the pandemic now in most people’s rear-view mirrors, 1Day Sooner has transformed itself into a forceful advocate of challenge trials for many other infections — as well as a supporter of trial participants. “There are a lot of diseases besides COVID-19 where ‘one day sooner’ means saving lives,” argues Josh Morrison, the group’s president and co-founder, who is based in New York City. The group, which says it now has a roster of more than 42,000 people in 166 countries who have expressed an interest in challenge trials, is the biggest organized effort to champion such trials and their participants.

Controlled human-infection models, as scientists call challenge trials, were already on the rise. A 2022 systematic survey identified 284 human challenge trials conducted since 1980, encompassing more than 14,000 participants, with the number of trials almost doubling from the 2000s to the 2010s1. The trials involve gaining consent from volunteers, who are typically healthy and young, and intentionally infecting them in a clinic, where researchers can monitor symptoms and administer treatment if needed. This can help to test the effectiveness of vaccines and treatments quickly and cost-effectively in controlled conditions, before moving on to time-consuming and expensive field trials, which involve enrolling participants and waiting for enough of them to develop a particular infection. For instance, a malaria vaccine endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) last month proved its effectiveness in challenge trials before going on to field testing. As with some other clinical trials, such as those testing an experimental drug’s safety, participants in challenge trials are usually compensated financially.

Some researchers who have conducted or are aiming to launch challenge trials are starting to work with 1Day Sooner, seeking input on aspects such as volunteer compensation. In September, 1Day Sooner joined dozens of scientists, physicians and other public-health experts to publish a letter arguing that human challenge trials are crucial to developing a vaccine against hepatitis C2. If the trials go ahead, it will partly be thanks to 1Day Sooner’s advocacy, some researchers say.

But conducting such trials involves ethical scrutiny of the potential benefits and risks. The broad consensus among research ethicists is that the trials are permissible only if the benefits are great, the risk to participants is low and the knowledge they provide could not easily be gained from other studies. Some researchers have questioned whether a 2021 challenge trial of COVID-19 that 1Day Sooner advocated was worth the risk to participants, given that there were more than enough natural infections to adequately test vaccines and treatments at the time. “That challenge trial was a bit of a damp squib,” says Charles Weijer, a bioethicist at Western University in London, Canada, who is unconvinced that challenge trials were appropriate during the pandemic. “I thought it was reckless and unnecessary.”

Should scientists infect healthy people with the coronavirus to test vaccines?

Some researchers also worry that 1Day Sooner’s laser-like focus on challenge trials could lead to missed opportunities to involve people in other types of medical study. Others are concerned that some participants might not fully appreciate the health risks or might be overly incentivized by the high financial compensation that the group has proposed for some trials.

Helen McShane, an infectious-disease researcher at the University of Oxford, UK, who is leading a COVID-19 challenge trial, says she has found 1Day Sooner’s advocacy helpful, particularly for recruitment. But she and her colleagues already seek input from participants in their trials and keep them updated on findings, McShane says. “I wouldn’t want an advocacy organization for volunteers to replace volunteers having their own voice.”

Acts of altruism

Backing challenge trials wasn’t Morrison’s first foray into advocacy — or altruism. In 2011, he says, he donated his left kidney to a stranger. “It made me feel better than anything else to think I had saved a life,” he says. He is a member of the ‘effective altruism’ movement, which advocates doing the most good with financial donations or other altruistic acts. He later stopped working as a corporate lawyer and, in 2014, co-founded Waitlist Zero, a group that advocates on behalf of living kidney donors.

Morrison was locked down in his Brooklyn apartment during the pandemic when he became interested in challenge trials. He read a March 2020 article arguing that SARS-CoV-2 challenge trials could be done ethically by limiting them to healthy, young people who are at low risk of serious disease, and that they might hasten vaccine development3. He started wondering whether he could help by advocating on behalf of potential participants in COVID-19 challenge trials. “I thought about it overnight and immediately felt like this could be the most important thing I could do in my life,” Morrison says.

Hundreds of people volunteer to be infected with coronavirus

Morrison quickly co-founded 1Day Sooner with infectious-disease epidemiologist Sophie Rose, who is now a biosecurity policy adviser at the Centre for Long-Term Resilience in London, UK, and Julia Murdza, 1Day Sooner’s chief operating officer. They started a petition for COVID-19 challenge trials in late March 2020 and, by September 2020, 38,000 people in 166 countries had signed up. A scientific survey of a subset of these volunteers found that they tended to be well off, highly educated and motivated mainly by altruism4. Some, such as Morrison, were part of the effective-altruism community. But the group isn’t monolithic, says Alastair Fraser-Urquhart, an undergraduate at University College London who participated in the first COVID-19 challenge trial. “1Day Sooner is a collection of volunteers who think different things,” he says.

The group talked to scientists hoping to run such trials, staged debates and town-hall meetings and promoted the idea to politicians in the United States and the United Kingdom, where COVID-19 challenge trials were being seriously considered. When the first such trial went ahead in 2021, led by researchers at Imperial College London, it involved 34 participants aged 18–30 and included volunteers such as Fraser-Urquhart, who had signed 1Day Sooner’s petition.

By then, COVID-19 vaccines had been proved to be highly effective in conventional clinical trials. The goals of the Imperial trial were to establish what dose of SARS-CoV-2 could reliably infect participants and cause only mild or moderate disease — a key first step in the development of any challenge model — as well as to study the dynamics of infection.

The Imperial study showed that a surprisingly small dose of COVID-19 could infect about half of participants, and that rapid antigen tests identified when people were infectious, even when they didn’t have symptoms5. Of those who became infected, all developed mild or moderate disease, and five reported disturbances to their sense of smell that lasted at least six months after infection. A longer-term follow-up study is planned.

Dozens to be deliberately infected with coronavirus in UK ‘human challenge’ trials

A second UK challenge study, which gave SARS-CoV-2 to people who had previously had COVID-19, is expected to report its results in the next few months. McShane says COVID-19 human challenge studies have been demonstrated to be safe, adding that the two UK studies have been justified by providing valuable data, and that they could further identify immune responses that help people to fend off the virus.

But Weijer is not the only bioethicist to have raised concerns about COVID-19 challenge trials. The findings might have been a let-down to the thousands of people who answered 1Day Sooner’s call, says Seema Shah, a bioethicist at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, Illinois. Challenge trials, she says, “didn’t make as much difference as those people were hoping or expecting”. Shah worries that the group’s focus on challenge trials was misplaced, and thinks it might have made more of a difference if it had helped to address gaps in recruitment for COVID-19 vaccine trials, such as the exclusion of pregnant people.

Morrison stands by the ethical arguments for COVID-19 challenge trials, but says he didn’t fully appreciate the scientific complexity and time involved in running them, especially during a pandemic; it can take more than a year to develop a challenge model before vaccines and treatments can even be tested. He still hopes that such trials can help to test next-generation COVID-19 vaccines, by providing a clearer read-out of their efficacy — especially in terms of reducing transmission and mild disease — than would be possible with field trials. But if SARS-CoV-2 challenge trials yield only scientific insights into the virus and don’t contribute to better vaccines, it will be a missed opportunity, Morrison concedes.

Chronic challenge

Intentionally infecting someone with hepatitis C virus (HCV) as part of a human challenge trial would have once been “in the category of ‘no, you can’t possibly do that’,” says Weijer, because the health risks were too great. Left untreated, chronic HCV infections can cause cirrhosis, liver failure and death. By contrast, other pathogens typically tested in challenge trials have involved short-term, lower-risk infections.

But in the past decade, the ethical equation for HCV has changed because of a new generation of antiviral drugs that have a cure rate approaching 100% — meaning they leave almost no detectable virus. This makes a challenge trial conceivable, researchers say. With the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic waning — alongside interest from participants in challenge trials, say investigators — Morrison wanted 1Day Sooner to identify a way of showcasing the potential of challenge trials to make a difference in global health. The group’s continued focus on challenge studies stems from the trials’ track record of delivering advances in this field, Morrison says. The potential risks of these trials and the demands they put on participants tend to be greater than for most other studies, creating the need for an advocacy group such as 1Day Sooner, he argues.

The next generation of coronavirus vaccines: a graphical guide

The group consulted with infectious-disease specialists and ultimately decided to focus on HCV after Morrison read a 2021 article co-authored by leading HCV experts, including Charles Rice, a virologist who shared the 2020 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology for discovering HCV6.

HCV is responsible for 1.5 million new infections and 290,000 deaths each year, according to the WHO. Antiviral drugs are effective but costly, and have to be taken for up to several months, so researchers are seeking a vaccine. But enrolling people who are at risk of HCV infection, such as users of injection drugs, in vaccine trials has proved difficult, hindering vaccine development. The push for HCV vaccines was dealt a blow in 2021, when a trial involving hundreds of injection drug users showed that a once-promising vaccine was ineffective7. Now, Rice and other HCV specialists argue that challenge trials involving volunteers could be the only realistic path to a vaccine.

1Day Sooner started advocating for HCV trials in 2021 and reran its COVID-19 playbook — organizing workshops, writing open letters and opinion pieces and lining up would-be participants. “It’s a chance to learn from the COVID experience and find places that we can do better,” says Morrison. The group has even helped to broker potential funding for trials in Oxford, UK, and in Toronto, Canada, from Open Philanthropy, a non-profit organization aligned with effective altruism in San Francisco, California, that has provided around 40% of 1Day Sooner’s support as part of its funding for global health.

“The time is right to make this happen,” says Ellie Barnes, an immunologist and liver specialist at the University of Oxford, who would lead the HCV challenge trial there. “Without this, it will be impossible to progress the vaccine field.”

Ethical scrutiny

Testing HCV vaccines could mean leaving people infected for up to 4–6 months, says Jake Liang, a physician–scientist at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland. About one-quarter of HCV infections go away naturally, and a too-short infection period could mask a vaccine’s true efficacy against chronic infection. Any trial would have to pass ethical scrutiny before it can proceed. “If we’re going to do this, we’re going to do it right,” says Liang.

If HCV challenge trials do go ahead — which could happen as early as 2024 — Morrison would like to see 1Day Sooner and its participants have a say in how they are run. A survey of people in the group’s registry found strong support for HCV trials and a willingness to endure being infected for several months, particularly if it meant that results would provide a clearer signal of vaccine efficacy or trials would require fewer participants. Respondents’ main motivation for thinking about participation was to help others, but most saw no conflict between this and being well compensated8.

The authors of the study, most of whom are employed by or affiliated with 1Day Sooner, proposed that participants should be compensated around US$20,000 for a six-month trial, a significant jump from the £2,000–5,000 (US$2,500–6,200) or so that challenge studies usually offer. They also said that plans for how the trial will be conducted should be made public — a step they have campaigned for with COVID-19 trials — and that results should be disseminated quickly and openly to maximize their benefit to society.

Hearing the views of potential trial participants has been helpful, says Barnes. She is interested in the idea of improving compensation for volunteers but worries that large sums could be seen as unduly inducing participation and might not gain ethical approval in the United Kingdom. “Paying somebody £15,000 — that is a potentially life-changing amount of money,” she says.

No clash with cash

Scholl sees no conflict between his desire to do good and the $4,875 he received for taking part in the Zika challenge trial. “The two things I want are a successful Zika vaccine and money,” he says. “It feels a little crass saying the latter, but I’m a grad student. I don’t make much.”

Scientist deliberately gave women Zika — here’s why

The itchiness notwithstanding, Scholl says he didn’t mind his nine days in quarantine during the trial, which was run at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. The Wi-Fi was good, he says, and it gave him a chance to catch up on his reading and films. The fatigue he experienced is now gone. Researchers first proposed Zika challenge trials during the 2015–16 outbreak, but they were considered ethically acceptable only once their value clearly outweighed the risks, says Shah, who led a 2017 ethical review of the proposal.

Morrison thinks that giving trial participants such as Scholl a greater say in how studies are run will ultimately benefit research by encouraging a greater number of better-engaged volunteers to take part. His long-term vision is for 1Day Sooner to become a union for research volunteers that, while promoting research that is valuable to society and arguing for better pay and working conditions, emphasizes participants’ agency and their right to take part on their own terms.

The group doesn’t accept funding from drug or vaccine makers, but recent events have shone a spotlight on some of its financing. In 2022, it received $375,000 from the FTX Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the collapsed cryptocurrency exchange FTX. Sam Bankman-Fried, the co-founder of FTX, was convicted of wire fraud and other charges stemming from his role at the firm in early November.

Morrison says the group is in the process of returning the money, and that the experience has led it to be more diligent about investigating potential supporters. Many of its funders — who have contributed a total of $7.8 million as of July 2023 — are philanthropies linked to the technology industry, including Open Philanthropy, which is largely funded by Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz and his wife Cari Tuna.

One of Morrison’s biggest worries is that 1Day Sooner hasn’t yet justified the investment. The group is now expanding beyond challenge trials: one idea is to stimulate research into effective ways of improving indoor air quality to reduce transmission of airborne pathogens. A spin-off group called 1Day Africa (which was to be partly funded by the donation from the FTX Foundation) aims to improve vaccine equity and empower study participants on the continent.

“What keeps me up at night? I don’t feel yet that we’ve had a significant win,” Morrison says. “It only matters if you accomplish something.”