Commandos on Wings” ran the headline of the article in Washington’s Evening Star on November 1, 1942. The subhead read, “They are Uncle Sam’s glider troops, who drop silently out of the sky, seize airfields, blow up bridges and ammunition dumps.” The article included a quote from Brig. Gen. James Doolittle, hero of his eponymous air raid on Japan the previous April. “Don’t forget the boys without motors,” he said. “They will be the spearhead of future Airborne attacks.”

Yet a decade later the U.S. Army removed gliders from its arsenal. They had been rendered obsolete by the evolution of the helicopter. Helicopters, not gliders, were the spearhead of future airborne attacks.

The combat life of the military glider was a short but adventurous one. Germany pioneered the use of gliders in warfare and was the first to deploy them in combat, using 41 gliders to capture Belgium’s Eben-Emael fortress on May 10, 1940, along with three bridges over the Albert Canal the fort protected. The Allies were impressed enough to initiate their own glider program. In the ensuing five years the Allies used gliders in some of the most famous operations of the war, including the invasions of Sicily, France and Germany. The engineless craft also served in the challenging terrain of the Burmese jungle.

However, their contributions, as well as the bravery of the men who piloted the craft and those who trained as glider infantry, have not received the recognition they deserve. “It has just been overlooked,” reflected Flight Officer George E. Buckley of the 434th Troop Carrier Group, 74th Troop Carrier Squadron, in a 2007 documentary entitled Silent Wings. “People never heard of them. People to this day, that were old enough during World War II to know about things, say, ‘Gliders? I didn’t know they used gliders.’”

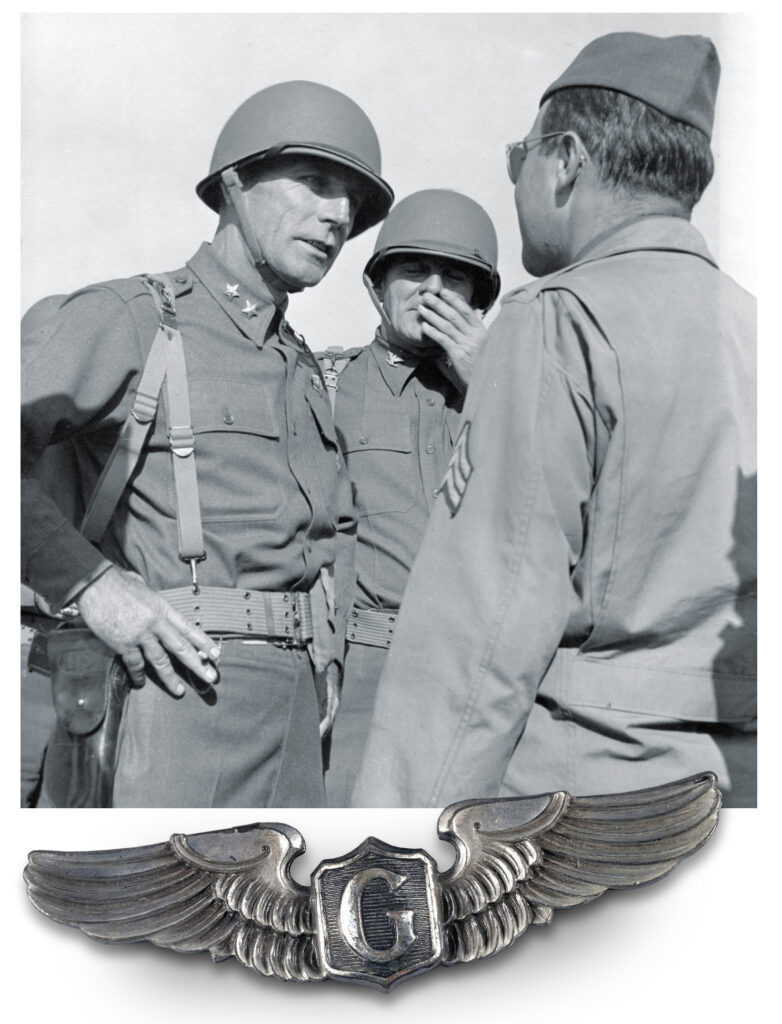

(Special Collections/NC State University Library; HistoryNet Archives)

America came late to the concept of airborne warfare. It wasn’t until May 1, 1939, that the U.S. chief of staff, General George C. Marshall, sent a memo to Maj. Gen. George Lynch, his chief of infantry, entitled “Air Infantry.” Lynch’s instructions were “to make a study for the purpose of determining the desirability of organizing, training, and conducting tests of a small detachment of air infantry with a view to ascertaining whether or not our Army should contain a unit or units of this nature.”

Lynch replied swiftly and positively, concluding that air infantry had practicable uses, but other priorities sidelined the project until after war in Europe erupted in September 1939. In January 1940 Marshall made the development of an air infantry a priority, and to lead its formation and development he assigned Major William C. Lee, a veteran of World War I. Today Lee is referred to as the “Father of the American Airborne,” and it is said that when the 101st Airborne Division jumped into Normandy in the early hours of June 6, 1944, they did so with a yell of “Bill Lee.” But Lee was also influential in the evolution of America’s military glider.

In his seminal book Paratrooper!, Gerard Devlin—an airborne veteran of Korea and Vietnam—wrote that for Lee the glider “represented a means of delivering troop reinforcements and supplies to his parachute troops once they had landed in remote areas. Equally important, the glider was an aerial vehicle for the delivery of large caliber weapons and light wheeled vehicles.”

The first step toward reaching that goal was to select a manufacturer from the several prototypes that were being tested at Wright Field in Ohio. The model chosen was the Waco CG-4A glider, which was 49 feet in length and had a wingspan of 84 feet. Its load-carrying capacity was 4,000 pounds, which equated to two pilots and 13 combat soldiers.

(David Rowlands/Cranston Fine Arts)

Actual gliders weren’t available until October 1942, so in the interim the recruits in the glider training program had to improvise. Larry Kubale was a newly qualified flight officer when he volunteered for gliders in the middle of 1942. “At that point they didn’t have anything other than sail planes,” he recalled. “Cargo gliders weren’t even invented at that point. After about seven weeks of that stuff, I was an instructor in sail planes, and had about sixteen students in four classes.”

The pilots underwent glider training at one of three centers in Missouri, Nebraska and North Carolina, and by the end of the war 10,000 of them had qualified. The 88th Infantry Airborne Battalion became the United States’ first glider infantry unit in May 1942. Later designated the 88th Glider Infantry Regiment, it was the first of 11 such regiments that served in the war. It wasn’t a volunteer system. Soldiers were assigned to glider regiments and, to their chagrin, they didn’t get the $50 dollars a month extra pay that paratroopers received on account of their hazardous duty. There were other resentments. “We weren’t even allowed jump boots,” recalled Ernest Platz of the 327th Glider Infantry, 101st Airborne Division. “It was a point of honor that the glider men could not use parachute jump boots.”

The glider men finally received their jump boots when they were shipped overseas, and in time they earned the respect of the paratroopers as well. “I talked with the paratroopers,” said Platz. “They would never go into combat under the gliders because if there’s a plane that was hit, they had a chance to get out by their parachute. But if we were hit, that was it. You had no way, except to crash land. So we got a little respect from them.” Eventually, in July 1944, after representations had been made to Congress, the glider men began receiving the same pay as the paratroopers did.

By that time the glider men had proved their courage and effectiveness.

The Allies’ first major glider operation of the war was codenamed Ladbroke. It was an Anglo-American mission launched on the night of July 9-10, 1943. The destination was the eastern coast of Sicily, where 1,600 men of the 1st Airlanding Brigade were to land ahead of the main invasion force and seize several key objectives, including the Ponte Grande bridge just outside Syracuse.

A total of 144 gliders, 136 of them CG-4As, took off from Tunisia, towed by C-47 Dakota tug planes of the American 51st Troop Carrier Wing as well a handful of RAF Albemarle bombers.

(©Corbis via Getty Images)

The glider pilots were all British. One of them was Staff Sgt. Alec Waldron of the 1st Battalion Glider Pilot Regiment. To his consternation, Waldron found himself behind the controls of an American Waco CG-4A, known to the British as the CG-4 Hadrian. Waldron had trained on a British Airspeed Horsa. “The Hadrian glider was quite a different aircraft to the Horsa,” he reflected. “It had a lower wing loading, carried about half the load—15 people—had a flat angle of approach, lift spoilers, small flaps and was certainly not ideal from a military point of view.” For the Ladbroke operation, the gliders would cast off at pre-determined heights and simply “glide in more or less dead stick to the landing zones.”

Waldron feared the operation “would be a disaster,” and he was right. In many respects it was doomed from the outset. The crews of the C-47s were inadequately trained and, in some cases, of inferior quality to the airmen assigned to bomber and fighter squadrons. It was a similar story for British glider pilots with virtually no experience of night flying and little opportunity to familiarize themselves with the CG-4A glider.

As the aerial armada sighted Sicily, the glider tugs began ascending to 6,000 feet, the release altitude for the gliders. Simultaneously vessels of the Allied invasion force spotted them and opened fire in the belief they were Axis aircraft. Confusion, panic and inexperience resulted in most of the glider pilots cutting themselves loose prematurely. Ninety of the 144 gliders crashed into the sea south of Sicily, and hundreds of men drowned.

Waldron’s glider came down in the sea about 400 yards from the shore, enabling the soldiers inside his craft to swim to the beach. “I couldn’t swim,” he said. “I floated on a wing…they were machine-gunning us down a searchlight beam and I got a ricochet through my thigh.”

After Waldron spent about seven hours in the water an Allied vessel picked him up and transported him to a hospital in Malta.

Paul Gale from Brooklyn was a navigator in one of the C-47s and recalled that none of the crews had been trained properly for such a hazardous night mission. Their instructions were to release the gliders 3,000 yards from the shore but, he reflected, “How the devil do you know when you are 3,000 yards from shore at night without any instrumentation?” Nor were there Pathfinders ashore to light up the landing zones. “There is no fixed point of reference,” he said. “You can see the shoreline maybe, but we had never had any practice.”

(James Dietz ©2023)

Nonetheless 12 gliders did land close to the target, with 83 British soldiers, enough to seize the Ponte Grande bridge.

Overall, however, and certainly in terms of lives lost, the Sicilian operation was a failure, a result of inexperience and a poor chain of command. But in March 1944 another Anglo-American glider operation provided an audacious example of how gliders could transport special forces behind enemy lines.

The Chindits were a British unit raised in 1942 by the unorthodox general Orde Wingate. His second-in-command was Michael Calvert, nicknamed “Mad Mike.” The first Chindits operation was a long-range reconnaissance patrol behind Japanese lines in Burma in early 1943. A year later their task was to carry out guerrilla raids against the enemy in Northern Burma to support General Joseph Stilwell’s major offensive there. The Chindits would use CG-4A gliders towed by C-47s of Colonel Phil Cochran’s 1st Air Commando Group to penetrate deep into the Burmese jungle. Sixty-two gliders took off from Lalaghat on March 5 and 35 of them covered the 400 miles to the target. Calvert was aboard one of the gliders and recalled the moment the tow line was cut. “The Dakota’s engines faded away and a tremendous silence enveloped us, weird and frightening after the sound of the familiar and comforting machinery that had carried us through the air,” he wrote. He glanced at the glider pilot, a gum-chewing American named Lees, “who sat relaxed as if driving a Cadillac on a wide American motorway.”

Three hundred and fifty Chindits landed safely, along with a bulldozer brought in to clear the landing strip of glider detritus. Over the next few days Dakota troop carriers made scores of landings, bringing in 9,000 men, 1,500 mules and 250 tons of equipment. Wingate issued an order of the day in which he declared the Chindits “are inside the enemy’s guts.” Calvert concurred. “Thanks to the Air Force boys we were, indeed, inside the enemy’s guts and it was now up to us to start giving him a stomach-ache.”

The British and Americans heeded the costly errors of Operation Ladbroke in Sicily as they planned for Operation Overlord, the invasion of northern France in early 1944. Tug and glider pilots received more thorough training, and the wings and fuselage of the gliders were painted in black and white stripes so Allied naval gunners could identify them.

(National Archives)

In addition to the nearly 300 CG-4A gliders available for Overlord, there were more than 500 British Horsa gliders, which could carry two pilots and 30 fully equipped troops. The plywood Horsa was also considered more maneuverable on account of its large “barn-door” flaps that made it easier for pilots to execute steep descents onto smaller landing zones. The Horsa had a tricycle undercarriage for takeoff. Once airborne, the pilot would jettison the wheels and use a sprung skid under the fuselage for landing. It had a hinged nose to make loading and unloading of cargo easier, as well as a reinforced floor and double nose wheels to support vehicle weight. Despite the improvements over the CG-4As, the British gave their Horsa a nickname: the “silent coffin.”

The landing precision of the Horsa was brilliantly demonstrated at 16 minutes past midnight on June 6 when Major John Howard and 180 men of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry glided to earth beside two small bridges over the River Orne (Ranville Bridge) and Caen Canal (Bénouville Bridge) in Normandy. The operation was codenamed “Deadstick” and beforehand its pilots had practiced landings in southern England. One thing they concluded was that 28—not 30—soldiers was the correct payload capacity based on each fully-equipped man weighing 240 pounds.

One factor was left to luck: the number and location of the Nazis’ anti-glider obstacles, dubbed “Rommel’s Asparagus.” These were thick poles sunk into the ground at intervals of 15 to 40 feet and intended to spear unfortunate gliders.

Howard was in the lead glider, which was piloted by Staff Sgt. Jim Wallwork. At seven minutes past midnight, Wallwork released the nylon towline from the tug aircraft. For the next seven minutes he piloted the glider down from 6,000 feet to just over 500, reducing the airspeed as he did so from 160 mph to 110 mph. As he approached the landing zone, Wallwork shouted over his shoulder to the men sitting in rows along both sides of the fuselage. “Brace!” The 28 soldiers linked arms and raised their legs to reduce the risk of breaking them during the landing. “The look on his face was one that one could never forget,” said Howard of Wallwork as the glider came in to land. “I could see those damn great footballs of sweat across his forehead and all over his face.”

When the glider hit French soil it was more a crash than a landing. The soldiers crawled out of the glider just 30 yards from Bénouville Bridge. Lieutenant Den Brotheridge was shot dead at the head of his men, the first Allied fatality of D-Day, but within 10 minutes the target had been secured.

(Popperfoto via Getty Images)

Late on D-Day, after tens of thousands of Allied soldiers had landed in Normandy by parachute or landing craft, gliders were used en masse to resupply the troops fighting to secure the beachhead. Nearly 250 gliders came down on two landing zones near Caen to reinforce the British Airborne Division, while to the west 176 gliders, part of Operation Elmira, descended inland from Utah Beach, a couple of miles south of the village of Sainte-Mère-Église, onto a landing zone just over a mile in length and 500 meters wide that covered both the 82nd and 101st Airborne sectors.

Most of the gliders—140—were Horsas and one of the pilots was Larry Kubale. In his glider was a jeep, a trailer loaded with munitions and ten men. “They figured that fifty percent of us wouldn’t make France, and of the fifty that made it half of them would be coming back after it was over,” he recalled.

Kubale’s glider came down in a field but careered on until it hit some trees. The impact sheared off the wings and catapulted the copilot out of the aircraft. “The guy flying with us, he went right through the nose of the glider,” remembered Kubale. “He had the control in his hands…and he went right through the nose, the steering column in his hands and foot still on the rudder.” The copilot suffered a broken leg.

Kubale’s work was far from over. Having helped bring in the reinforcements, he now became one of them in the field. “The guys that I had with me, they were actually paratroopers, with the 101st Airborne, so I was with them for about four or five days,” he said. By the time it was over, Operation Elmira resupplied the American Airborne with 1,190 troops, 67 jeeps and 24 howitzers. Casualties, compared to the Sicily operation, were light, with 157 troops killed or wounded, and 26 of the 352 pilots killed or injured.

There were other significant Allied glider operations in 1944, in southern France and in the Netherlands. In France, more than 400 Horsa and CG-4A gliders were used for Operation Dragoon on August 15, landing some 20 miles inland to prevent the Germans from disrupting the landings. The Holland action was part of Operation Market Garden, intended to establish a bridgehead over the lower Rhine at Arnhem and open a pathway into Northern Germany. Despite the support by gliders, which transported more than 14,000 troops as well as weapons and supplies, the operation failed. The last mass use of gliders was for Operation Varsity on March 24, 1945, when the American 17th Airborne Division and the British 6th used more than 900 gliders to pass over the Rhine into Germany. Overall, 21,680 paratroopers and glider men landed on a total of 10 zones in 1,696 jump planes and 1,346 gliders.

(James Dietz ©2023)

Among the U.S. regiments participating in Varsity was the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment, whose instructions were to land just north of Wesel and seize the crossing over the Issel River. The ground fire was murderous as they approached the landing zones; twelve C-47 tug aircraft were shot down just after releasing their gliders and another 140 were damaged to varying degrees. Nineteen-year-old John J. Schumacher was in one of the gliders. He was in a double tow—two gliders behind a single C-47—with his jeep and his passenger. He remembered terrible turbulence cause by four traffic lines of aircraft, and something else. “There was an unusual sound as you went along that it took a little while to figure out what it was, but it sounded like popcorn,” he remembered. “It was bullets and shrapnel going through the wings of the glider…pop, pop, pop.”

As they neared the landing zone the glider pilots were presented with a new problem—poor visibility caused by crashed and burning aircraft plus a smoke screen laid down by the British. Nonetheless, Schumacher’s glider pilots managed to get the craft down in one piece and then helped him lift up the tail and get the nose lowered enough so they could open it and release the jeep.

Another glider used in Operation Varsity was the General Aircraft GL.49 Hamilcar. Intro-duced on D-Day, it was the biggest craft of its kind that the Allies deployed during the war. It had a wingspan of 110 feet and a length of 68 feet and could carry a payload of 36,000 pounds, which meant it could carry either two Bren Gun Carriers or one small Tetrarch tank. The Hamilcar was never again used in combat after Operation Varsity.

In 1946 gliders began to be phased out of the American military. Their contribution to the war effort faded from memory, unlike that of the more glamorous and gung-ho paratroopers. “It’s aggravating,” admitted George Buckley in the Silent Wings documentary. “And that is another reason I like to collect glider stuff and let people know about it.”

Glider pilots were a small and skilled band of brothers, whose perilous existence cultivated not only a camaraderie but also a sardonic humor, encapsulated by one of their favorite songs, “The Glider Riders.” Sung to the tune of “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze,” one of its verses ran:

We glide through the air in a tactical state,

Jumping is useless, it’s always too late,

No ’chute for the soldier who rides in a crate,

And the pay is exactly the same.