A photographic archive has been discovered in Lyon, France, that adds precious detail to what we know about the founding of the world’s first police crime laboratory in 1910 and its creator, Edmond Locard, a pioneer of forensic science.

The huge collection, which comprises more than 20,000 glass photographic plates that document the laboratory’s pioneering scientific methods, crime scenes and Locard’s personal correspondence, is thrilling historians at a time when many consider that forensic science has lost its way. “There is a movement to look back to the past for guidance as to how to renew the science of policing,” says Amos Frappa, a historian affiliated with the Sociological Research Centre on Law and Criminal Institutions in Paris, who is overseeing the analysis of the images.

She was convicted of killing her four children. Could a gene mutation set her free?

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many people in Europe and beyond were thinking about how criminals might be accurately identified by using techniques such as fingerprint, blood and skeletal analysis. Locard was the first person to create the semblance of forensic science. He established the first scientific lab that came under the aegis of the police, and that was dedicated to studying ‘traces’ of criminal activity collected from crime scenes.

Garage find

The collection of photographic plates almost didn’t survive. It languished for decades in a garage belonging to the National Forensic Police Department in Ecully, a Lyon suburb. In 2005, the glass plates were rescued from the garage and stored in Lyon’s municipal archives. But at the time, the Lyon archives lacked the resources to treat the collection properly, says director Louis Faivre d’Arcier. It wasn’t until 2017 that an inspection revealed that the plates’ gelatine layer containing the image information was, in many cases, infected with mould. After a sorting and decontamination project in 2022, conservators saved around two-thirds of the plates.

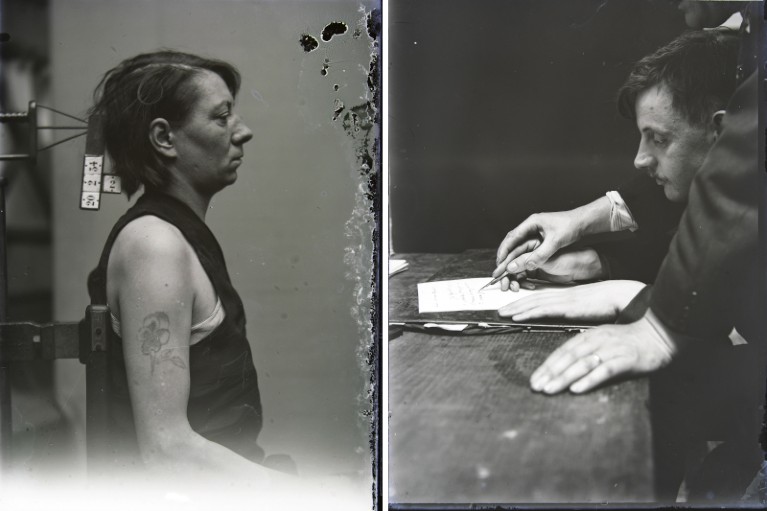

Left: A tattooed woman named Marie-Clémentine in 1934; Edmond Locard’s team used tattoos as a way of identifying potential criminals. Right: Handwriting analysis as a means of identification was investigated but later spurned by Locard, who deemed it unreliable.Credit: Archives municipales de Lyon

The mammoth task of digitizing the contents of the fragile plates, which are mostly unindexed and disordered, became possible only when a local publisher and historian of funerary practices, Nicolas Delestre, offered to finance it. In collaboration with the municipal archives, his team developed a photographic protocol to capture as much information from the plates as possible. The digitization will be completed this spring, to coincide with the publication of Frappa’s French-language biography of Locard. The slow rebuilding of the indexes continues.

Locard, who worked in the early to mid-twentieth century, is famous for his maxim, which is usually formulated in English as “Every contact leaves a trace.” Trained as a forensic pathologist, he turned to the study of trace evidence after a French political scandal called the Dreyfus affair, in which a Jewish army officer called Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of espionage. During the affair, Locard’s mentor Alphonse Bertillon, who had invented a method of identifying people through bodily measurements, was called on as a handwriting specialist, despite having no expertise in the field. He wrongly identified Dreyfus as the author of an incriminating note.

Forensic science: The soil sleuth

Locard, seeing other countries adopt fingerprint identification, embraced that method instead. In 1910, he set up his laboratory in the attic of Lyon’s main courthouse, and gradually expanded his scientific analyses to include traces such as blood, hair, dust and pollen.

Sherlock Holmes connection

This much was known from published sources, but the photographic archive offers details about the social and intellectual milieu that produced Locard, onthe scientific networks in which he was embedded, and on how his thinking evolved as he experimented and made errors. His exchanges with contemporaries in countries including Germany, Switzerland, Italy and the United States shaped his approach, which might be why he did not consider himself a founder of a new field. But Locard’s ideas — his scientific methods and his insistence on meticulously studying crime scenes — fell on fertile ground in Lyon’s police chiefs and judges, who, unlike their Parisian counterparts, accepted the evidence that such approaches generated. “Lyon was a receptacle,” says Frappa.

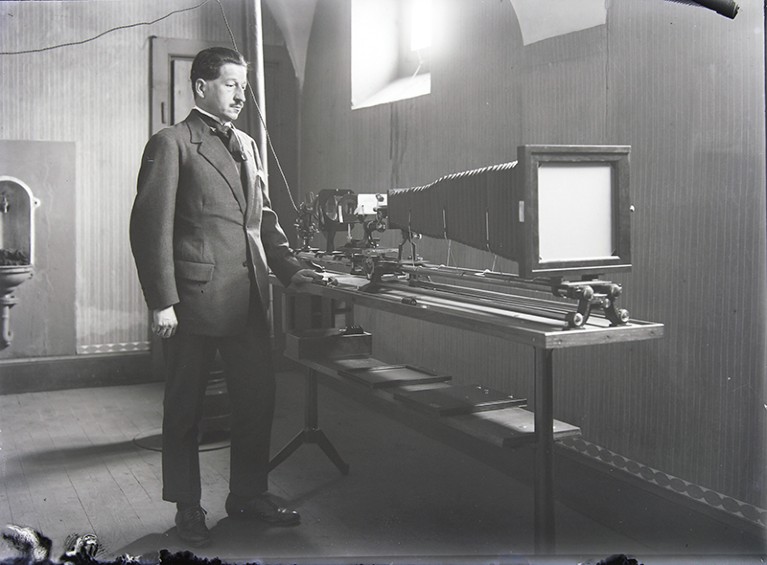

Edmond Locard using a photographic bench in the 1920s.Credit: Archives municipales de Lyon

The new collection reveals Locard’s team at work. It captures their equipment and experiments, and the forensic traces they analysed. The close-knit group socialized together, received international visitors and investigated myriad means by which people could be identified. One way was to look at people’s tattoos, and the collection contains a large set of tattoo images. Locard took inspiration from many sources, including the Lyon-based Lumière brothers, who were pioneers of cinematography, and the creator of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle, with whom he corresponded. In time, Locard discarded some techniques — notably, handwriting analysis — deeming them unreliable.

Since 2009, when a report from the US National Research Council found that many modern forensic techniques were inadequately grounded in science, the discipline has struggled to reorient itself. “By the late 20th century, it’s fair to say that forensic science had become an adjunct of law enforcement without allegiance to science,” says Simon Cole, who studies criminology, law and society at the University of California, Irvine, and directs the US National Registry of Exonerations. Cole has written about the problems with fingerprint identification, and last year reported on the fallibility of microscopic hair comparison. These techniques are routinely used to investigate crimes in the United States and elsewhere, and the evidence they generate is admissible in court.

Modern troubles

The 2009 report suggested that improving forensic science would require larger labs in which diverse specialists were insulated from each other and from the police to prevent bias. The trouble with that view, says Olivier Ribaux, director of the School of Criminal Sciences at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, is that, when considering the potentially infinite number of traces that a crime scene can generate, some subjective selection by humans is inevitable. To ensure that this selection is as informative and as unbiased as possible, the forensic scientist must understand a trace in its context — as Locard’s maxim in French originally implied. “The problem with the big labs is that they have severed the connection with the crime scene,” Ribaux says.

He favours an alternative model in which smaller labs employ generalists, who can oversee specialists in certain fields, such as ballistics and DNA, but can also offer a more holistic view of a case. These generalists would work closely with the police — a return to Locard’s approach, in other words. But the two aren’t mutually exclusive, Ribaux says. They are just snapshots of the ongoing debate about how the field should reinvent itself.

That debate will surely be fuelled by the emerging portrait of Locard, sometimes dubbed the French Sherlock Holmes, whom Frappa describes as “a man so visionary he predicted, correctly, that he would be forgotten”.