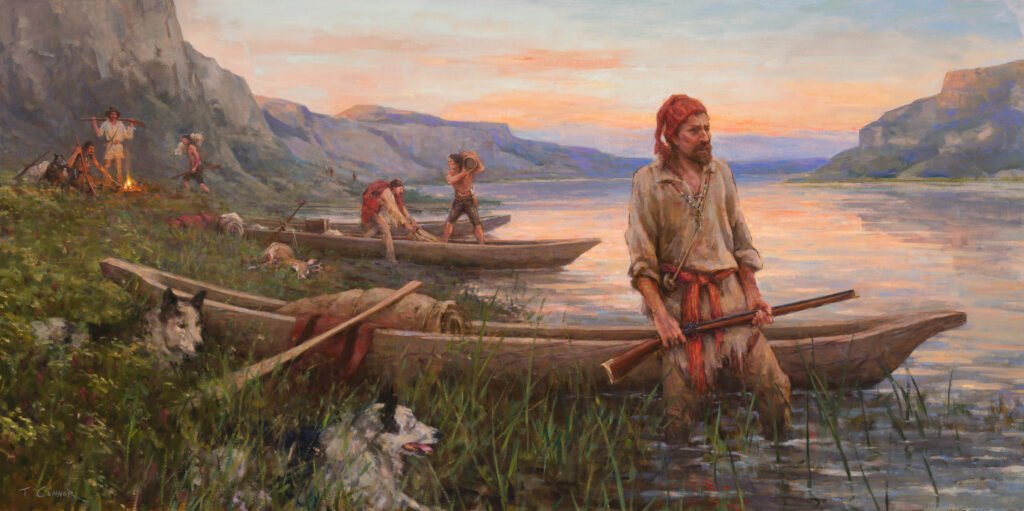

The landscape is lush with color, a riverside camp serene with its crackling fire and abundant provisions. In the foreground before his fur-laden canoe stands a trapper, rifle in hand, worry furrowing his brow as he looks downriver. The successful hunters and their resting dogs seem ready to settle into Camp on the Upper Missouri, but the scene also hints at an unknown future—and hidden violence.

The tension in artist Todd Connor’s work is indicative of the precipitous nature of the frontier West, and the depth Connor brings to the canvas reflects a lifetime spent looking below the surface.

(Courtesy Todd Connor, toddconnorstudio.com)

Connor [ToddConnorStudio.com] finished his first plein air painting at age 12 while visiting an eastern Oklahoma lake named Tenkiller, a locale that fueled the Tulsa native’s enthusiasm for exploration. “Plein air helps me see value, color and atmosphere properly and adds authenticity to my studio work,” he explains. A year later Connor’s passions took him to new depths, quite literally. “I got certified as a diver at the age of 13 with my dad. We had spent most of my childhood at the lakes and around water. I think my fascination was being below the surface.” Both encounters with nature helped shape the artist’s subsequent life and career.

In 1987, at age 23, Connor signed up for a tour with the Navy that lasted four years. “After high school I got the bug to join the service, specifically the Special Forces,” he says. “A coworker of my dad’s happened to be an ex–Vietnam UDT [Underwater Demolition Team] guy, who recommended SEALs, since I loved the water so much.” After an honorable discharge from the SEALs, Connor spent time visiting historical sites and exploring natural landscapes that renewed his interest in plein air painting.

“I’ve done hundreds of outdoor landscape paintings on-site and a few in the studio,” the artist says, “but I always wanted to tell the story of the American West. That led to learning to draw figures and horses in earnest, especially after visiting the Museum of Western Art in Kerrville, Texas.”

A roster of talented artists helped him get started. “I’m grateful to have had the best of mentors in both drawing and painting,” Connor says. “My earliest was Ginzie Chancey, of Tulsa. Then, in Los Angeles, there was Steve Huston for drawing; Dan Pinkham, Dan McCaw and Donald Puttman for painting; and Gary Carter, [a member and past president of] the Cowboy Artists of America. He pointed me in the right direction for proper training by suggesting the ArtCenter College of Design, in Pasadena.”

Connor’s work often features strong female figures—mothers, daughters and sisters juxtaposed against stark vistas of rugged beauty. “Strong women evoke the primal,” he explains. “A mother protecting her nest applies to the survival of all life on the planet. In that period it was often a woman who came between the family and the threat of danger. Men weren’t always around. They were farming or out hunting for long periods of time.”

His painting The Gathering Storm, for example, depicts a young mother standing sentinel outside her sod house, infant child cradled in one hand, a double-barreled shotgun in the other. In Far From Anywhere a mother sits with her two daughters on the bench seat of their covered wagon. Shielding her eyes from the setting sun, the woman gazes over a vast open plain.

(Courtesy Todd Connor, toddconnorstudio.com)

“The hardships and the teamwork it took to just stay alive is something our modern society seems to have lost touch with,” Connor says. “The family has been the foundation of humanity. I show it in the context of settling the frontier.”

In 2020 Connor moved to Fort Benton, Mont., one of the oldest settlements in the state, which served as inspiration for another of his favorite themes—the Lewis and Clark Expedition. “A fascinating story—an expedition going upriver with no motors through 2,000 miles of wilderness untouched by white men, not knowing what they would find or if they would return at all,” the artist says. “When I started painting for a living, it was coming up on the bicentennial of the expedition, and I did a series of paintings on the subject. In terms of complexity of story and number of figures and composition, it’s probably my most ambitious work to date.”

Connor had long been drawn to the history and beauty of the region. “I’d wanted to try living in old Montana since going there for 20 years to float the White Cliffs,” he says. “So many memories of being with my father and friends out there, and lots of plein air studies resulted from those trips over the years. We dressed up in 1800s costumes and created reference photos of trappers and traders, mountain men and their Indian counterparts with canoes, all against the stunning background of the cliffs and river. I’ve done many historical paintings from those shoots.”

(Courtesy Todd Connor, toddconnorstudio.com)

From his 2,700-foot home studio Connor paints every day and often into the night, referencing a sketchbook loaded with ideas.

“I also do miniature paintings, which I sell from my website or at shows where I have a booth, like the [C.M.] Russell Museum auction. These small pieces give me perspective on deciding whether a larger version would be interesting.” When an idea makes the cut for further development, Connor employs models to bring the project to fruition.

(Courtesy Todd Connor, toddconnorstudio.com)

Ironically, his success leaves him little time for his own works. “I am currently working on three commissions. I’m generally painting for show deadlines, the last one being the Briscoe Museum’s “Night of Artists” show. I like to be ahead with lots of ideas and options to choose from for any given exhibit, but the reality of the business is sometimes it’s pretty hard to keep up.”

Success also has its rewards. During a recent tenure as an artist in residence at Craig Barrett’s Triple Creek Ranch in Darby, Mont., Connor shared his love of painting with guests and squeezed in time for his own plein air work.

“Painting on-site is a learning experience,” he says, “an essential activity for every painter to do now and again in their career, in order to stay fresh and growing in your craft.”