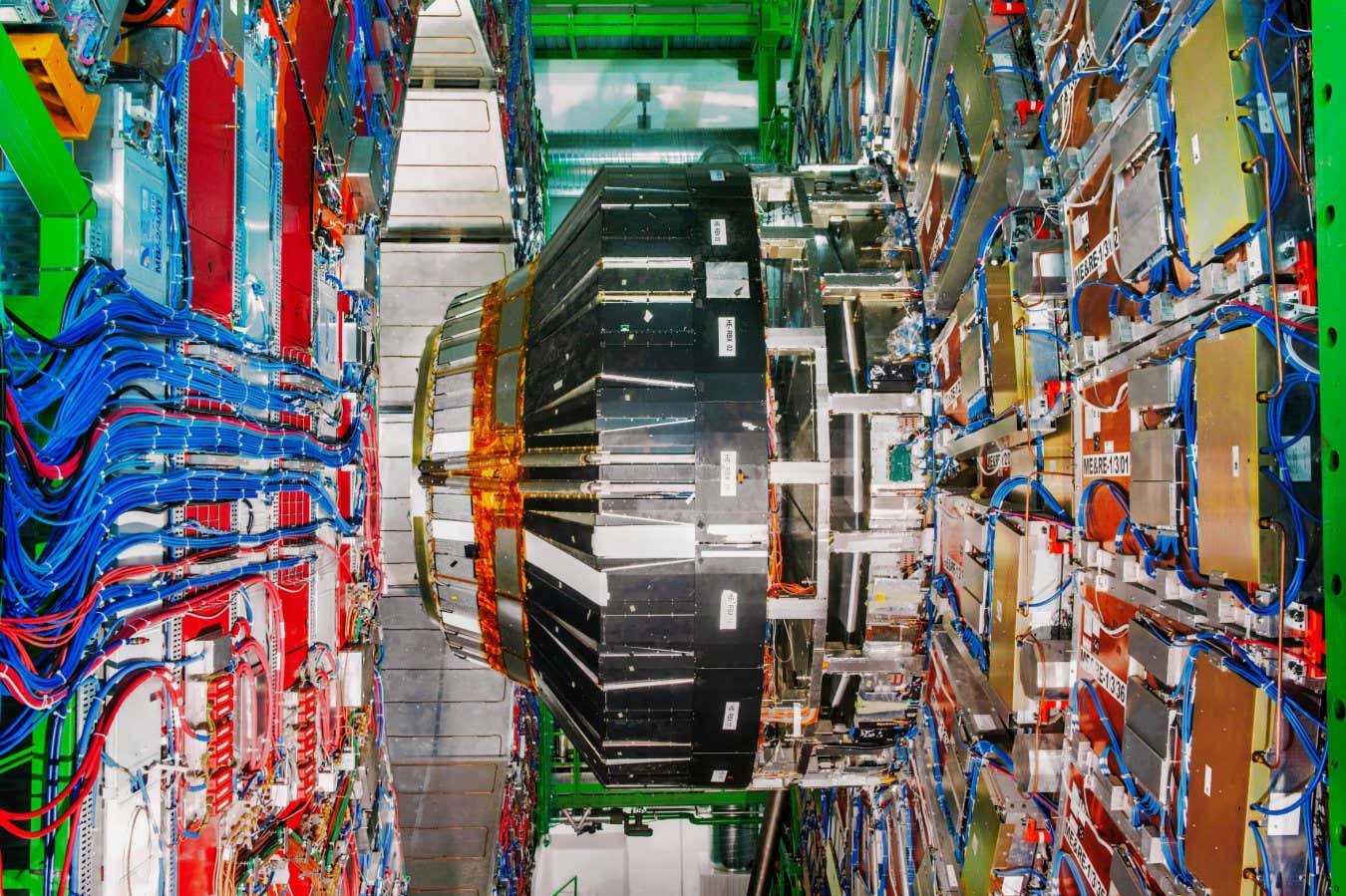

The CMS detector at the Large Hadron Collider

SciTech Image/James King-Holmes/Alamy Stock Photo

A possible crack in the standard model of particle physics seems to be shrinking, as new data from CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) contradicts a previous puzzling result that had physicists excited about the possibility of new, exotic physics – but some mysteries remain.

“The standard model survives for the moment,” Josh Bendavid at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology told a packed seminar room at CERN, the particle physics laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland, on 17 September. He was presenting new data on the mass of the W boson, a fundamental particle that is crucial for processes like nuclear decay and setting the mass of the Higgs boson.

Questions about the W boson mass began in 2022, when physicists working with data from the Tevatron collider at Fermilab in Illinois sent shockwaves through the particle physics community. Their value for the W boson mass was starkly different from that predicted by the standard model, our best picture of how the universe’s particles and forces interact, suggesting physicists may have missed something.

But in 2023, researchers at CERN cast doubt on this discrepancy, after they reanalysed old data taken by the ATLAS detector at the LHC. They found a value for the W boson mass that once again agreed with the standard model prediction, dampening hopes for a deviation from known physics.

Now, Bendavid and his colleagues have produced a new value for the W boson mass, using new data from another of the LHC’s detectors, the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS), and found a value of 80,353 million electronvolts (MeV) which, with an uncertainty of 6 MeV, agrees with the standard model. The tiny uncertainty also makes this the most precise measurement produced at the LHC, said Bendavid.

Ashutosh Kotwal at Duke University in North Carolina, who led the scientific collaboration that produced the Tevatron result, says that it is great to have another measurement of the W boson mass, but as the LHC and Tevatron colliders use different methods to produce the particle, it is harder to compare the results. However, Martijn Mulders at CERN, who is part of the CMS collaboration, says this difference will have been taken into account in the overall uncertainty.

“In this fundamental respect of the beams, ATLAS and CMS are identical,” says Kotwal. “What would have been ideal is additional or independent data at the Tevatron.” Unfortunately, the Tevatron shut down in 2011, so there will be no more new data.

All of this means it is too early to tell which W boson mass measurement is correct and that the differences must still be explained. “It doesn’t end with two numbers on the table, it’s the beginning,” says Kotwal. “It’s when we start discussing scientific and technical details about procedures. The truth is out there, there is a W boson mass in the universe. We’re all trying to find it.”

The model behind the CMS calculation differs from that used to obtain other results, says Matthias Schott at CERN, who works on the ATLAS collaboration. This makes its alignment with results that use other models a sign that it is more likely to be correct, he says. “This gives us extremely high confidence now,” says Schott. “All the measurements align so well within each other, except for the one which is just off, so I would tend to say that this solves the case.”

Mulders agrees that the onus is now on the Fermilab, or CDF, group to explain its result. “Most of my colleagues will now believe that these W boson mass result measurements agree with each other and with the standard model prediction, and that that is probably the real answer and the CDF result is an outlier,” says Mulders. Schott and his colleagues on ATLAS are currently preparing a completely new measurement of the W boson, also from new data, which should help settle the matter, he says.

Topics: